Up here at the northern extremity of the tube, other than being grateful for always getting a seat, I wonder how many commuters give much thought to how this stretch of the Northern Line evolved.

Unlike Charles Holden’s sleek art deco designs for neighbouring Piccadilly Line and other parts of the Northern Line (he was also responsible for East Finchley’s iconic station), our rather older over-ground railway feels more like a Victorian rural branch line. It certainly does if you sit facing the expanse of Green Belt countryside beyond the Dollis Brook and is particularly scenic when you’re travelling at sunset. At this point it doesn’t feel like the ‘Misery Line’ at all.

Although it now seems integral to the Northern Line, High Barnet was originally on a separate line. The station was built in 1872 (along with Totteridge and Whetstone and Woodside Park stations – West Finchley came later in 1933) by the Great Northern Railway Company (GNR), more famous for the mainline from London to York (1850). Their suburban network already included Finchley (Church End), Mill Hill East, Mill Hill The Hale and Edgware (1867), having taken over the Edgware, Highgate and London Railway Company in 1862. This created a line from Moorgate through Finsbury Park to Edgware and a separate spur to Broad Street. The remains of the stretch of line running through Muswell Hill and Crouch End can be seen today as the Parkland Walk. The last remaining part of this ‘Northern Heights’ railway is the spur to Mill Hill East which had originally continued to Edgware (with later plans to extend to Bushey Heath brought to an end by the Second World War and the introduction of the London Green Belt).

Establishing the Barnet terminus for the line turned out to be a complicated process. In the 1860s three rail companies submitted bids and locations considered were up on the hill near The Black Horse on Wood Street and behind Christ Church. Other options had included a site opposite Union Street (near the Star Coffee House) and behind Moxon Street. Land to the west of Barnet Hill near Underhill (opposite the current station) was also proposed, but the Wood Street location was the leading contender having been given the go-ahead in 1867. However, plans stalled for two years and the current location on the site of Barnet Races was settled on and works proceeded.

By 1923 the Great Northern Railway had become part of the London and North Eastern Railway and it wasn’t until 1939 that railway was connected to the Northern Line by a newly constructed tunnel to Archway (formerly known as Highgate station and hitherto the northern terminus of this branch) under the New Works Programme, replacing the LNER steam service in April 1940. The Northern Line had only been formed in 1937, four years after the formation of London Transport. It was the result of amalgamating the City and South London Railway (C&SLR) and the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway (CCE&HR or ‘Hampstead Tube’) which ran to Golders Green when it opened in 1907 and was extended to Edgware in the 1920s, with the branch from Camden to Highgate (renamed Archway).

The ‘Northern Heights’ route to Finsbury Park and Alexandra Palace was disconnected and the line to High Barnet electrified with East Finchley Station redeveloped with two sets of tracks and the two-level Highgate station was completed in 1941 (serving both tube and LNER trains), the same year that the main-line steam service was discontinued, with the last service to Alexandra Palace was in 1954. After several years’ occasional use for freight traffic, the line between Mill Hill East and Edgware was dismantled in 1965. The Copthall Railway Walk and the Mill Hill Old Railway Nature Reserve cover parts of this stretch.

The broad tentacles of this (rather complicated) line, became the Northern Line we know today and much of the current tube network was rationalised at this time, finally unifying a series of railways that had evolved since the mid 19th century.

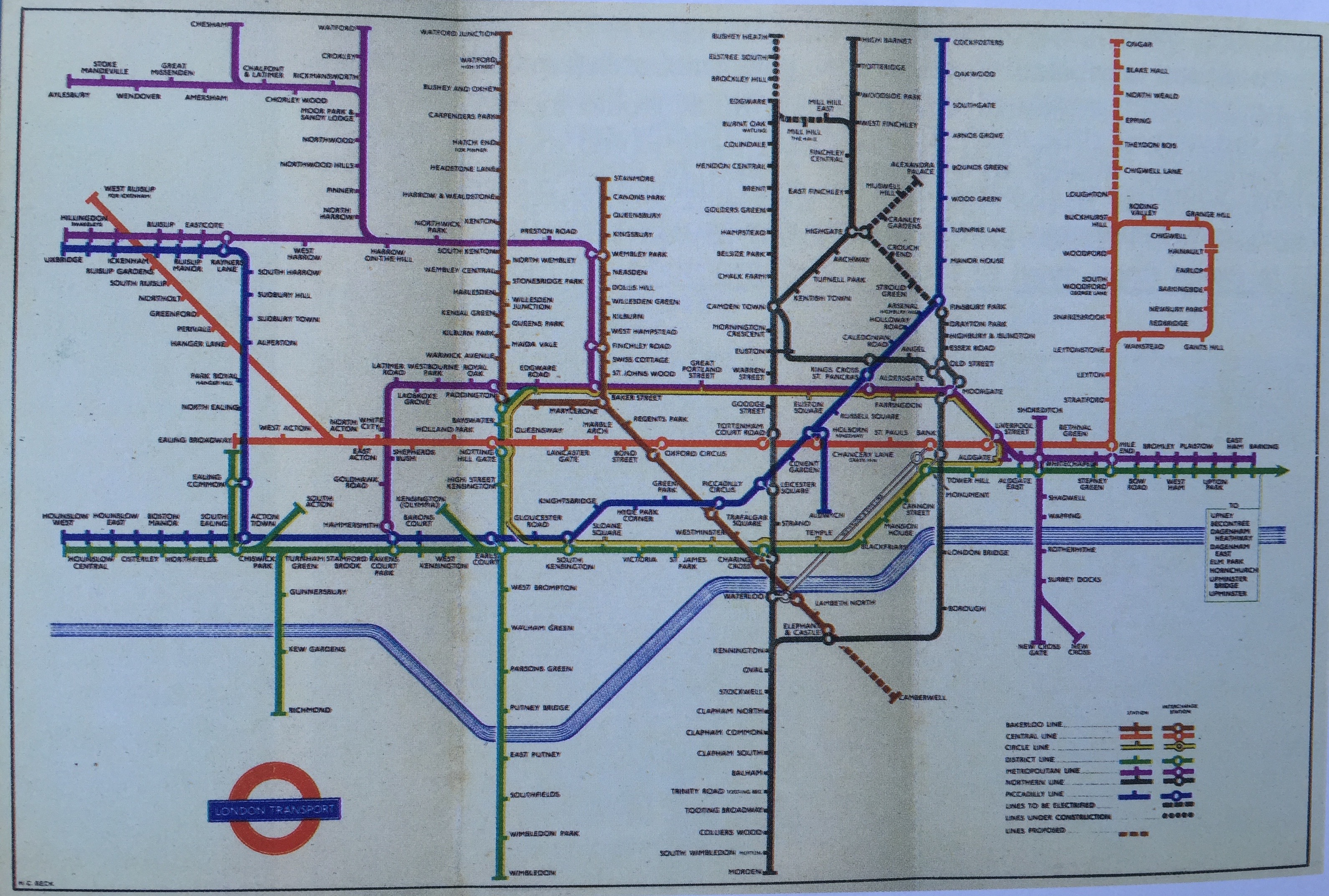

Here is a tube map from 1949 showing the ‘Northern Heights’ in their full complicated glory (along with planned extension to Bushey Heath). The map also shows reveals interesting plans at the southern end of the Bakerloo that were never realised.

There’s obviously a lot more information available on this subject, but a visit to the London Transport Museum is always worthwhile and Christian Wolmar’s The Subterranean Railway makes fascinating reading.